A groundbreaking study1 has raised the provocative question of whether the trauma of war can alter genes in ways that affect future generations. Focusing on Syrian refugees, the research found distinct genetic markers in families exposed to violence—patterns that persisted in their children and even grandchildren. While the findings open new avenues for understanding intergenerational trauma, scientists caution that the results are far from definitive.

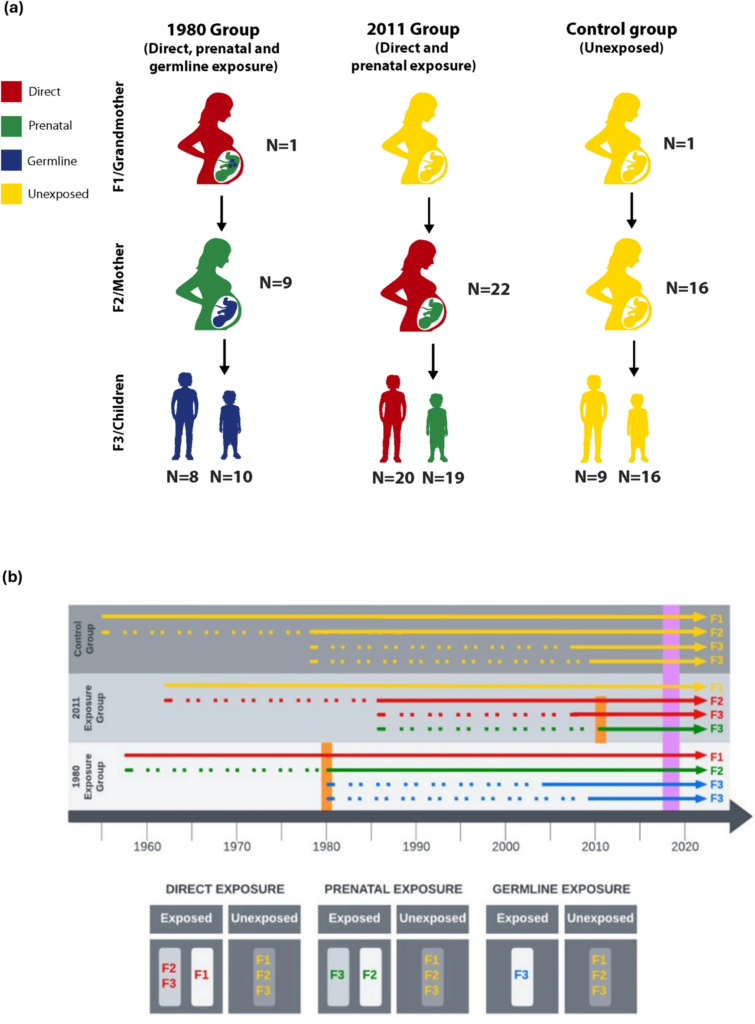

Published in Scientific Reports, the study explores epigenetic inheritance—changes in gene activity caused by environmental factors, such as trauma, without altering the DNA sequence itself. Researchers analyzed DNA methylation patterns in 10 families who fled Syria’s 1980s conflict, 22 families displaced by the 2011 uprising, and 16 families with no war exposure.

A Biological Legacy of War?

The analysis revealed unique methylation signatures in individuals who endured violence, with some markers appearing in their descendants. One striking case involved a grandmother who survived the 1982 Hama massacre, where Syrian forces killed tens of thousands. Her daughter and grandchildren carried similar epigenetic tags, suggesting a possible hereditary link to her trauma.

Participants exposed to post-2011 violence—including torture, persecution, and witnessing deaths—also showed distinct methylation patterns. Researchers conducted in-depth interviews to document their experiences, strengthening the connection between trauma and genetic changes.

Scientific Excitement—And Skepticism

Rachel Yehuda, a neuroscientist at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine, called the study a compelling “proof of concept” but stressed that it doesn’t prove trauma directly causes heritable changes.

We still don’t know how these markers influence health or behavior

Rachel Yehuda

Other experts remain doubtful. Michael Kobor, an epigeneticist at the University of British Columbia, questioned whether methylation marks could survive the body’s natural “reprogramming” during early development, which typically erases such changes.

A Growing Field with Unanswered Questions

The study builds on prior research into intergenerational trauma, including findings from Holocaust and Rwandan genocide survivors. Yet, the mechanisms behind epigenetic inheritance remain poorly understood, and replication studies are needed.

Molecular biologist Rana Dajani, a co-author of the study, argues that this research is a crucial step in uncovering war’s long-term biological effects. But for now, the debate continues—highlighting both the profound impact of violence and the mysteries of human genetics.

As science grapples with these questions, one thing is clear: the shadows of conflict may linger far longer than we ever imagined.

- Mulligan, C. J., Quinn, E. B., Hamadmad, D., Dutton, C. L., Nevell, L., Binder, A. M., Panter-Brick, C., & Dajani, R. (2025). Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees. Scientific Reports, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89818-z ↩︎